When an analogy may help our faith

Clarity comes through a faith we practice religiously

“I have told you this in figures of speech. The hour is coming when I will no longer speak to you in figures but I will tell you clearly about the Father.” (John 16:25)

Etymologists have determined many figures of speech, from the simple pun and the misleading euphemism to the confusing difference between an onomatopoeia and a polysyndeton. There are also cliches, oxymorons, and idioms that make for good fun. Dozens more complicated and spicy wordplay definitions fill the grammar books.

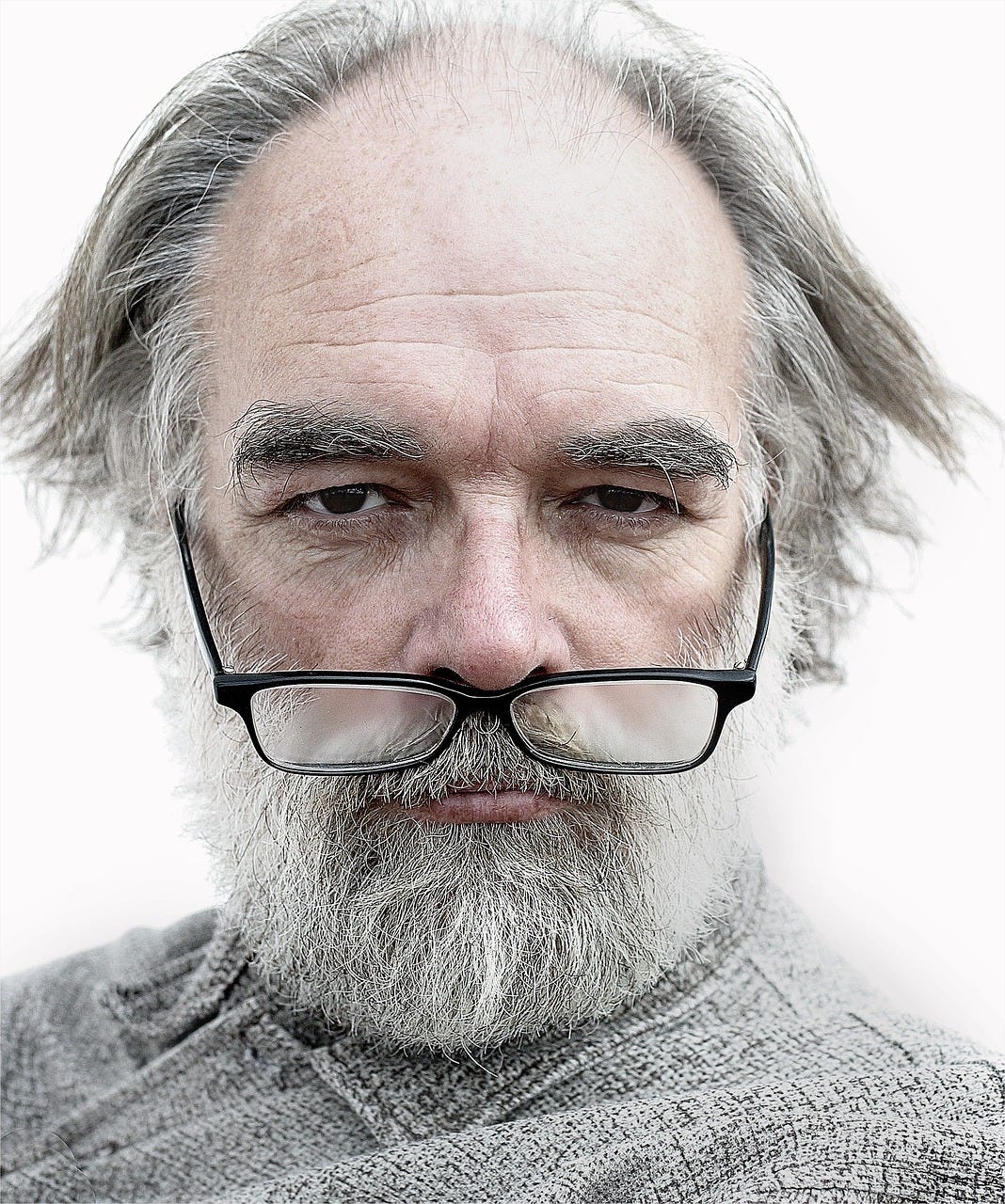

Image by Pexels

In his rhetoric and preaching, Jesus used many figure-of-speech mechanisms, such as metaphors, allegories, similes, analogies, and the occasional hyperbole. Further studies have found many more.

I’ve had trouble with similes, metaphors, and analogies. This is probably because I mix up their properties by using all three simultaneously, but mostly because there are so many ways to convey our thoughts that we need more than just one pair of glasses, so to speak.

For instance, I began my reflection today attempting to draw out the temporary, earthly necessity for religion, the institutional vehicle Jesus used to form the church. The clarity Jesus promised in the verses above would get muddied and twisted when he left them. He told the apostles this would happen. The apostles had clarity, then, but it would be attacked. Even though gathered and formed by the Holy Spirit, the initial church community would be broken into sects, and truth would be confused.

“I have told you this so that you might have peace in me. In the world you will have trouble, but take courage; I have conquered the world” (John 16:25). The function of religion is for the Holy Spirit to sustain and nurture us so that we are reminded to return and be welcomed back. Religion is necessary.

As a return to figure of speech, I came up with the following analogy, affirming religion as both necessary and helpful for our clarity:

Priests are our optometrists, correcting our eyesight and catching diseases before they destroy our vision altogether. Theologians are our ophthalmologists, studying scripture, traditions, and church documents, pointing out the imperfections in heresies, and arming apologists with a solid diagnosis of our faith’s doctrines. The eyeglasses we must wear as our eyes fail us are the sacraments and testimonies we must faithfully use to see our God.

Unless we insist on looking down our noses.

That’s about as far as the analogy goes without becoming silly or scrupulous.

Where analogies readily fall apart upon further scrutiny, a simile using the ophthalmology framework may last longer:

We attend to our souls as to our eyesight. The priest studies our heart like an optometrist. Theologians are as persistent and dedicated as ophthalmologists.

Metaphors can be so broad that they last forever. For example, if our faith goes blind, Jesus can restore our vision.

The allegory of optometry as religion’s metaphor/simile/analogy, a gift itself, is an example of the power of the figure of speech to convey a difficult idea.

We don’t live in clarity. Faith isn’t a formula. It’s not even a way of life. We need religion to live out our faith in this existence, fraught with temptations and difficulties that distance us from God. Our religious attachment, like glasses offered in various forms to focus our vision, close and far away, is necessary to distinguish God from everyone and everything else.

The ocular comparison of an invasive instrument attached to our heads to keep us from bumping into walls helps to “clarify” that our Catholic Church assists in a necessary and holy observation of faith.

A key function of the Evangelical movement, born from Protestant roots, was to identify the failures of denominational excess. They questioned the crust of institutional rust, prominent in mainline churches and, so they assumed, the Catholic enterprise. They claim that Jesus was anti-religion, so we should avoid the shackles of religious affliction. But even Evangelical faith communities operate with every element of religion’s necessary correction of secular blindness to God. Like any good religious endeavor, they include preaching, scripture study, acknowledgment and formal testimony of grace, and even the sacramental holy institutions of forgiveness, bread and wine, and ordination.

Some of us cringe at the idea of religion’s necessity. Clear paths to God, though, is not an endeavor that we can individually accomplish. That’s not how God made us. Instead of decrying the character limitations of our priests, the annoying frailties of our fellow Catholics, and the lack of professionalism in everything from modern church architecture to the lax faith of so many, put on your glasses of faith — whether wire-framed, frilly, tri-focal, lasered, corneally implanted, or monocled.

The religious obligations and excruciating detail we accept when joining a human-fraught religion will direct our lenses toward God. When we Catholics poorly subscribe to the physical good and the spiritually holy, that’s on us. We need only get out our bifocals, plop in our contacts, and wrap our faces with the grace of faith.

Clarity is good. Take care of your eyes.